Launched December 2022

Editors’ Note

Editors’ Note

For our first-ever themed submission call, we asked for your help-inspired manifestations. And you answered with prose, poetry and art that demands attention.

“Make noise until someone listens! Scream if you have to!” writes Hollay Ghadery in “Shalimar.” The voices in this volume call out, scream and cry for help from family, friends, partners, teachers, neighbours and even strangers. The work in this volume nudges us to consider what it means to ask for, receive and give help—and also, to deny it.

Now, it would be unwise if we didn’t address the theme because its selection wasn’t arbitrary. untethered needs your help.

Over the past eight years, untethered’s tiny team has lovingly laboured over thirteen print issues that featured an eclectic mix of quality prose, poetry, visual art and those strange beings in- between, on a next-to-nothing budget provided to us by the sheer generosity of our readers.

Like many other small, unfunded arts organizations, the pandemic hit us hard. We are flat out broke, but we aren’t giving up. In order for untethered to continue on as one of the most “disarming lit mags out there,” we need the help of our community now more than ever.

Submit to our submission calls, like and share our posts on social media, advertise with us on our website, donate (every bit really does help!), order some back issues or grab a subscription, come out to our launch events and tell all your friends about us!

YOU! YES, YOU! You can help untethered to keep doing what we do!

Sick Rats in the Apocalypse

M.E. Boothby

Sitting side-by-side on a futon in which Matilda has chewed a few small holes, the thought of apocalypse does not scare Laura and I as much as perhaps it should. We have come of age in a time where the end-of-days of popular imagination has gradually become more fact than fiction. We have never had the option of being willfully ignorant. To us, the apocalypse was always coming. The apocalypse is already here. There is nowhere to go. Our generation is often critiqued for its apathy. And yes, perhaps many of us have grown hopeless, but I would argue that hopelessness is not apathy. We’re not indifferent; our idealism has been ground down by bureaucracy and politics, waitlists and budgets. Each night, we weather visions of innocents murdered, of icecaps melting and wildfires burning, the slow violence of our deaths already underway. This is grief, not laziness. Without faith in the girders of long-broken human systems, we, the young, are left asking ourselves: what can I really do? What is within my negligible power? In the paralysis of the global pandemic, many of us have come to rest, like an empty shell drifting down to the seafloor, in the realm of the small. What small good can I put out into the world today? What small help? We can only do what we can do. And so, Laura and I care for sick rats.

This is Death’s Elegy

A love poem

Kelly S. Thompson

What are sisters for? Let’s fight emotion in your funeral order form familiar chubby cursive, tiny hearts checking scant boxes— bare bones for your bones. Crack open ribs to find the funny one dainty forefinger and thumb pluck at the t-shirt I made you— Making cancer my bitch since 1982, black words bolded— winking a sea green eye with oceanic tears. Let’s aim high. Encourage astronaut dreams, a bucket list to be proud of travel to places with coconut trees and mangoes, frozen in time, drink sanity with mojitos, set our bodies to balter until your wound parts like an open mouth stitches burping pearls of blood. And we’ll laugh at this, at the maracas rattling an anthem to our misread celebration. Let’s play pretend—remember? When it was easy? We were She-Ra and He-Man magic swords slicing through good and bad alighting a universe where your hair still bounces cellulite buckles on meaty thighs skin tinted peach instead of puce and you’ll heal through sheer force of will because we lean into overripe ballad lines drizzled on caviar. Let’s hold hands for this next part. Your absence forms cast iron anvils in my guts. You bubbled lies into potions that executrix duties could stave swells of whys and hows and onelasttimes squinting into the kaleidoscope of phosphenes riding morphine ponies until my own eyelids seal.

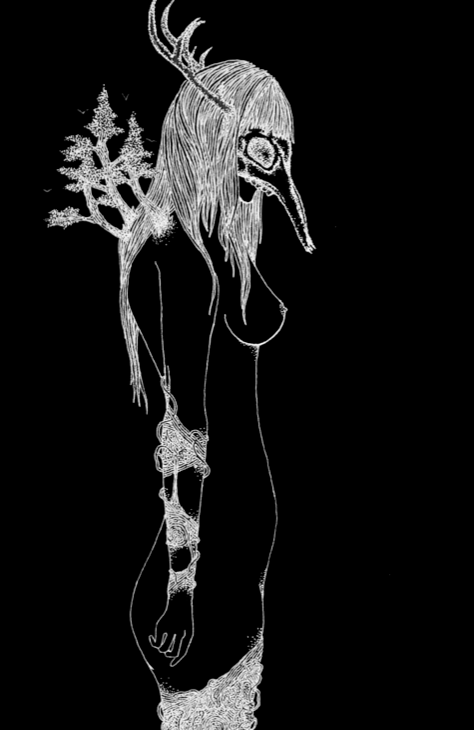

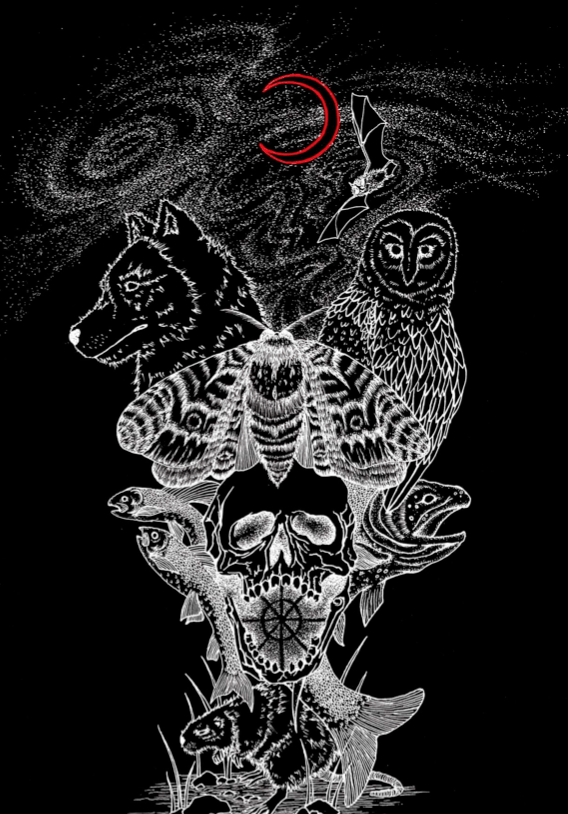

untitled | jed toejam

Shalimar

Hollay Ghadery

When I was trying to get pregnant, I told Mitra I knew something was wrong. The usual tests came back normal, but my uterus ached, all the time. I was losing hair, developing acne. We were in her sunroom; me sprawled like seaweed on a wicker couch, and Mitra at her piano, a sturdy maple upright. It was her first big purchase after she arrived from Tehran in the eighties. She’d been leafing through sheet music, picking pieces for students working toward exams. “Joonam, you need to make noise!” She slammed her fists on the keys. “Make noise until someone listens! Scream if you have to!” She spun around, her eyes sparkling brandied light. “It’s not ladylike, but since when has being a lady got us anywhere?” She said this and I knew I’d fight: for a diagnosis, a treatment, then, hopefully, a child. “Scream if you have to,” I told her that day in the kitchen. Her nose twitched, then she nodded sharply, just once. When I bent down to hug her goodbye, her perfume mingled with the rancid smell of hunger escaping her mouth.

for my sisters of the Asian diasporas

by Samantha Louie-Poon

When our existence evolves into water leaking down sister’s cheek, we then recount our steps, musing every thought that led us here. They did this— Our mundane tasks they diligently exoticized; Our struggles they ceaselessly sexualized; Our bodies authorized, owned by men who take day trips along the curves of our spine; enough to tender our limbs, becoming unraveled. Bones shatter beneath the impenetrable weight; they break and remodel our marrow into a submissive beast that lingers in the mirror when naked. Our flesh becomes their place for pleasure excursions and cheap labour. They tame us caged in a stranger’s body, we perform for the white gaze; our fragmented cries fester with nowhere to escape vanishing our last desire for selfhood. Helplessly, we relearn the foreignness of our bodies, every crevasse, curve, and scar; markers convincing us we were objects to be fetishized by wandering white eyes. After ten thousand more of our bodies civilized, we became relics only archaeologists uncovered. They wondered how our bones lay scattered beneath earth’s surface invisibly marked: anti-Asian hate crime our deaths not etched into blank pages of the State’s history books. But we know.

untitled | jed toejam

Silhouette

Beth Goobie

Philly was lean and quick, an exclamation mark among the gentler, rounder questions of other girls. Straight brown hair tumbled down her back, parted at the centre without bangs. She wore no makeup and stuck mostly to jeans and a t-shirt; her appearance scored on the pretty side of ordinary, but unremarkable. Still, there was something in the way she carried herself, like a speech continually building to its climax. And her curiosity was nuanced, sneaky, somewhere between a mind on tiptoe and a sniper. She held out the blouse—white cheesecloth with an embroidered bodice and long flared sleeves. Semi-transparent, it was a garment that could not be worn to church unless sanctioned by a camisole. As Claire accepted the blouse from Philly, she felt electricity lean out between them. Stepping away from the window, she pulled off her t-shirt. On their first night in this room, Philly had made a point of undressing and walking around naked, and Claire had gotten the message. Now, facing her roommate, she paused in her bra, defined from the waist up by anticipation. Claire’s chin jutted, her eyes held Philly’s as she unhooked and slid off the bra. Letting it drop to the floor, she pulled on the sheer, virgin- white caress. It was like slipping into a dream, like one of those pastel, light-blurred magazine photographs of a woman in a long flowing dress, standing in a blossomy meadow, each flower a blooming nerve. Claire was shorter and broader-boned than Philly; the blouse clutched at her shoulders, the hemline skirted her mid-thigh. She hesitated, her fingers curving under the hem, then unzipped her jeans and kicked them off, along with her panties. Air swooped in, kissing her skin and setting it on high alert.

no room for exiles

Alexander Holleberg

I have wrapped my dreams in a silken cloth . . . / Where long will cling the lips of the moth —Countee Cullen, “For a Poet” I cannot touch your dreams, though maybe I can help to keep the moths away a little longer—my bubbe’s recipe of cedar shavings, lavender, and lemon balm seems to work. Your dreams will smell of garden, though pleasant, a simulacrum of the planting that never comes to pass and a reminder of decaying things that make a garden grow. Her garden drawers repelled us, the scent affixing itself to the fact of old age, a threatening symbiosis dispersing us about the house—as if time would not infect us too, transmuted into remembering things. Hers were not dreams like yours, deferred, unpromised but maybe their ramet, the bouquet of passenger manifests, yellow identity cards and telegrams, a scattered testimony both formless and formal. How ready we were to avoid those drawers, to sneer at any hint of cedar, exile ourselves in rooms and make no room for exiles in afternoon games, as if imagining the dreams of others—of you, of bubbe—were not the stuff of childhood. Still, we consume: always searching for silk, the soft architecture of better dreamers, weavers of less earthly gardens.

untitled | jed toejam

This issue includes new work by Susan Alexander, Christine Barkley, M.E. Boothby, Franklin K.R. Cline, Doris Corcese, Leah Duarte, Hollay Ghadery, Beth Goobie, Tikva Hecht, Alexander Hollenberg, Samantha Louie-Poon, Rob Omura, and Kelly S. Thompson.

Artwork by jed toejam.